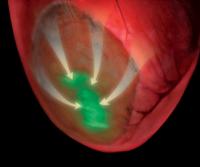

Cells implanted within damaged heart tissue (darker area) express a green fluorescent molecular sensor. Implantation of these cells, which express the protein connexin43, reduces the risk of the damaged heart developing fatal arrhythmias by enhancing electrical conduction (arrows). The fluorescent molecular sensor is activated when the cells contract, demonstrating conduction of electrical waves into the damaged area. Credit: Michael Simmons When researchers at Cornell, the University of Bonn and the University of Pittsburgh transplanted living embryonic heart cells into cardiac tissue of mice that had suffered heart attacks, the mice became resistant to cardiac arrhythmias, thereby avoiding one of the most dangerous and fatal consequences of heart attacks.

The discovery, reported in this week's issue of Nature, has profound implications for using cell-transplant therapies to restore damaged heart tissue.

The researchers, including Michael Kotlikoff, the Austin O. Hooey Dean of Cornell's College of Veterinary Medicine, one of the paper's senior authors, discovered that a protein called connexin43, expressed by the transplanted embryonic heart cells, improved electrical connections to other heart cells. The researchers showed that the improved connections helped activate the transplanted cells deep within the damaged section of the heart tissue. The technique reversed the risk of developing ventricular arrhythmias after a heart attack, the number one cause of sudden death in the Western world.

In the past, scientists have transplanted a variety of cell types into failing hearts with modest improvement of function, although transplanting skeletal muscle cells made things worse and led to more arrhythmias. Surprisingly, when co-author Bernd Fleischmann at the University of Bonn and colleagues transplanted embryonic cardiac cells, the hearts' electrical stability and function returned to normal.

Scientists recognize the untapped potential of using cell-based therapies to counter many debilitating diseases, but they have not had tools to assess the function of the cells once transferred. In Kotlikoff's laboratory, the researchers determined that the transplanted embryonic cells were making electrical connections with normal heart cells. Using genetically modified heart cells that express a fluorescent sensor, they established that transplanted heart cells were activated during normal heart contractions.

"For the first time we were able to see how cells used in therapy are working with other cells in a complex organ within a living animal, establishing the mechanism of the therapeutic effect," Kotlikoff said.

Professor Guy Salama at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine was also able to map voltage signals across the surface of the hearts, establishing that the implanted cells improve conduction of electrical signals within the damaged heart tissue.

While doctors could never use cells from a human embryonic heart for transplantation, researchers at the University of Bonn engineered skeletal muscle to express connexin43 and achieved the same restorative results as they did with the embryonic heart cells.

"These results have important implications for therapy, although they must be verified in the context of naturally occurring heart damage," Kotlikoff said. "One can envision using a patient's own cells by deriving heart cells from stem cells to improve heart function and decrease arrhythmia risk."

Source : Cornell University Communications

Print Article

Print Article Mail to a Friend

Mail to a Friend