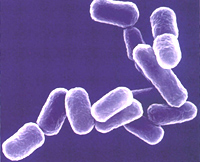

Bacteria feel pressures to evolve antibiotic resistance and other new abilities in response to a changing environment, and they react by 'stealing' genetic information from other better-adapted types of bacteria, according to research published in Nature Genetics today.

Bacteria feel pressures to evolve antibiotic resistance and other new abilities in response to a changing environment, and they react by 'stealing' genetic information from other better-adapted types of bacteria, according to research published in Nature Genetics today.

They do this through the bacterial equivalent of sex, otherwise known as horizontal gene transfer, through which bacteria obtain genetic material from their distant relatives. This allows them to evolve the networks of chemical reactions that enable them to do new things, such as defend themselves against antibiotics or antibacterial sprays.

In the first ever systematic study of how bacteria change their 'metabolic networks', researchers have been able to piece together the history of new metabolic genes acquired by the E.coli bacterium over the last several 100 million years.

They estimate that approximately 25 of E.coli's roughly 900 metabolic genes have been added into its network through horizontal gene transfer in the last 100 million years. This compares to just one addition by the most common source of new genes in animals, gene duplication, where copies of genes are made by accident and then altered over time.

To test why these new genes were needed by E.coli, the researchers cross examined dozens of E.coli's closest bacterial relatives to see which genes were most commonly exchanged between them. This would highlight the genes that have contributed the most to the evolution of metabolic networks across bacteria.

They found that most of these genes helped bacteria cope with specific environments. Thus, new genes were needed for new functions, not to make the bacteria better at what they were doing anyway.

"Metabolic networks are systems of interacting proteins, which perform the chemistry with which a bacterium builds its own components," said Dr Martin Lercher from the University of Bath who lead the study.

"Bacteria often acquire new genes by direct transfer from other types of bacteria; in a way, that's the bacterial world's sex, and it plays a crucial role in how pathogenic bacteria acquire resistance to antibiotics.

"For the first time, we have analysed how this mechanism allows complete metabolic networks to change over evolutionary time.

"We found that bacteria use new genes not to improve their performance in the environments they already know, but to adapt to new or changing environments; and accordingly, genetic changes happen at their interface with the environment.

"Bacteria feel pressures to change in response to a changing world, and they react by 'stealing' genetic information from other, better adapted, types of bacteria. In this way, bacteria are just as lazy as humans: why invent the wheel twice if someone else has already found a solution to your problem?"

The research also involved scientists from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (Germany), Eötvös Lorànd University (Budapest) and the University of Manchester (UK).

Source : University of Bath

Print Article

Print Article Mail to a Friend

Mail to a Friend