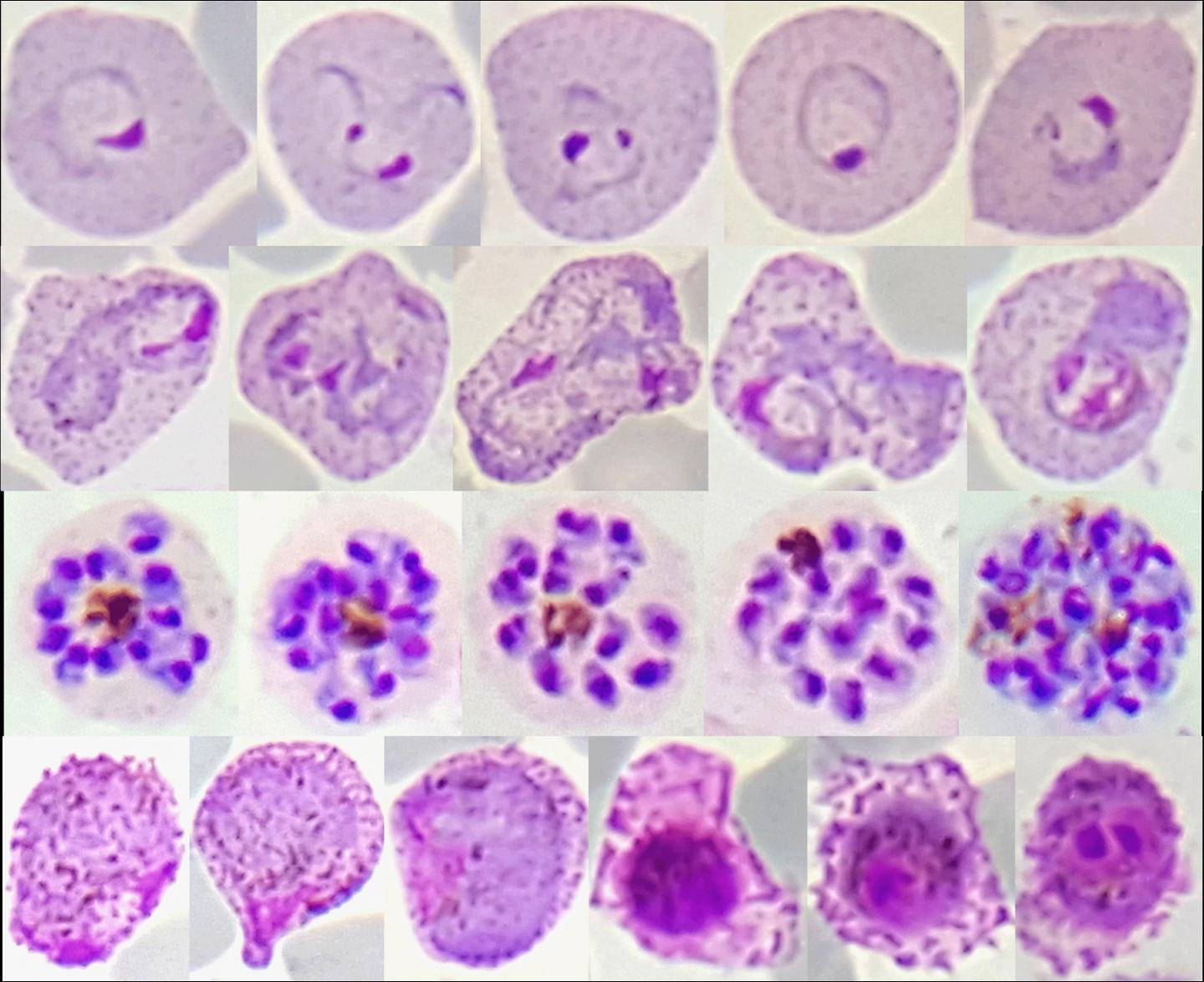

Red blood cell stages of Plasmodium vivax from malaria patients in Thailand. Plasmodium vivax (P. vivax) parasites, which cause a debilitating form of malaria, are yielding their secrets to an international team of researchers funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health. In the largest such effort to date, the team determined complete genomes of nearly 200 P. vivax strains that recently infected people in eight countries. Comparative analysis showed the parasites clustered into four genetically distinct populations that provide insights into the movement of P. vivax over time and suggest how it is still adapting to regional variations in both the mosquitoes that transmit it and the humans it infects.

"P. vivax malaria has historically been overshadowed by the more lethal disease caused by P. falciparum parasites," said NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, M.D. "However, there are some 16 million cases of clinical malaria due to P. vivax infection worldwide each year, imposing a large public health burden on many countries. The wealth of genomic information provided by this new research shows the high degree of genetic variability in the P. vivax population and gives us a clearer picture of the challenges we face in developing drugs or vaccines against it."

The study, published in Nature Genetics, was led by Jane Carlton, Ph.D., of New York University, and Daniel Neafsey, Ph.D., of the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

P. vivax parasites have several characteristics that make controlling or eliminating them difficult, Dr. Carlton notes. For example, a dormant form of the parasite can hide in the liver for months at a time, emerging sporadically to cause a fresh bout of fever and weakness in the infected person. P. vivax, she added, cannot be grown in the lab, making it harder to study than other malaria-causing parasite species. Furthermore, the rich genetic diversity of P. vivax strains in most geographic regions sampled means that no single drug or vaccine could be effective against the majority of strains in any one area, much less against all P. vivax strains worldwide. For these reasons, "the research community has always known that P. vivax would be the last malaria parasite standing," said Dr. Carlton.

Dr. Carlton led a team that determined the first genetic sequence of a strain of P. vivax in 2008. In 2012, Drs. Carlton and Neafsey and their colleagues added four additional genomes and determined that P. vivax parasites have twice the genetic diversity of P. falciparum parasites from matched geographic regions. Those studies used P. vivax strains that were originally taken from malaria patients decades earlier and had been modified to grow in monkeys.

In contrast, the new study sequenced P. vivax strains from volunteer blood samples taken recently in eight countries, including Papua New Guinea, India, Thailand, Mexico and several in South and Central America. When added to the countries of origin of the monkey-adapted parasite strains, eleven different countries were represented in the new analysis. Investigators at the Broad Institute developed a technique to increase the amount of parasite DNA in red blood cells and separate it from the much more abundant human DNA also present. The technique allowed them to sequence parasite DNA and, ultimately, to determine near-complete genetic sequences for 182 parasite isolates, said Dr. Carlton. "We confirmed and expanded our earlier findings regarding the extreme genetic diversity in P. vivax compared with P. falciparum" she said.

The four distinct parasite populations the researchers identified clustered into two groups: parasites from New World countries (Brazil, Peru, Colombia and others) differed greatly from those of the Old World countries (Thailand, Myanmar, India and others). P. vivax isolates from Papua New Guinea were genetically distinct from elsewhere in Asia, while strains from Mexico formed a fourth genetic grouping. The strains from Mexico were the least genetically diverse, Dr. Carlton said, which may be because P. vivax cases have declined sharply in that country.

The genomes offer clues to the ways P. vivax has traveled the globe and adapted to mosquito species found in the new regions the parasite was carried to by European traders and colonialists. For example, the P. vivax populations in Central and South America are genetically diverse and distinct from all other sampled regions. This suggests that today's New World parasites may have originated from multiple European sites during the Colonial era and may be descended from now-extinct European parasite lineages.

Dr. Carlton noted the key role played by the NIAID-supported International Centers of Excellence for Malaria Research (ICEMRs) in the new genome study. Investigators from the ICEMR based in Papua New Guinea, for example, had the difficult job of keeping blood samples on dry ice in extremely remote locations, she said. "The study would not have been possible without the ongoing dedication of this large group of collaborators at the participating ICEMRs," Dr. Carlton said.

Source: NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Print Article

Print Article Mail to a Friend

Mail to a Friend