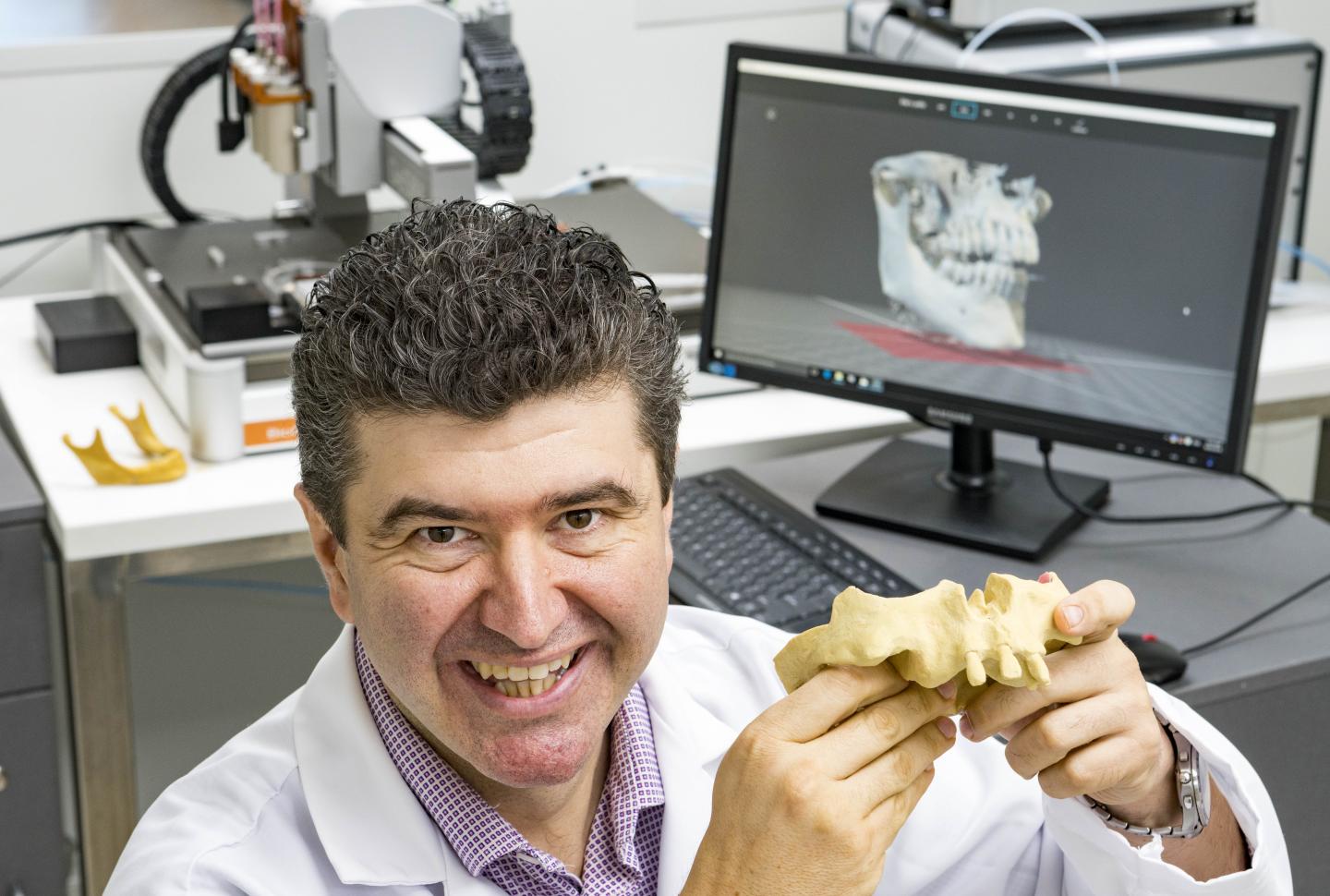

Professor Saso Ivanovski. The discomfort and stigma of loose or missing teeth could be a thing of the past as Griffith University researchers pioneer the use of 3D bioprinting to replace missing teeth and bone.

The three-year study, which has been granted a National Health and Medical Research Council Grant of $650,000, is being undertaken by periodontist Professor Saso Ivanovski from Griffith's Menzies Health Institute Queensland.

As part of an Australian first, Professor Ivanovski and his team are using the latest 3D bioprinting to produce new, totally 'bespoke,' tissue engineered bone and gum that can be implanted into a patient's jawbone.

"The groundbreaking approach begins with a scan of the affected jaw, prior to the design of a replacement part using computer-assisted design," he says.

"A specialised bioprinter, which is set at the correct physiological temperature (in order to avoid destroying cells and proteins) is then able to successfully fabricate the gum structures that have been lost to disease - bone, ligament and tooth cementum - in one single process. The cells, the extracellular matrix and other components that make up the bone and gum tissue are all included in the construct and can be manufactured to exactly fit the missing bone and gum for a particular individual.

"In the case of people with missing teeth who have lost a lot of jawbone due to disease or trauma, they would usually have these replaced with dental implants," he says.

"However, in many cases there is not enough bone for dental implant placement, and bone grafts are usually taken from another part of the body, usually their jaw, but occasionally it has to be obtained from their hip or skull.

"These procedures are often associated with significant pain, nerve damage and postoperative swelling, as well as extended time off work for the patient," says Professor Ivanovski. "In addition, this bone is limited in quantity.

"By using this sophisticated tissue engineering approach, we can instigate a much less invasive method of bone replacement. A big benefit for the patient is that the risks of complications using this method will be significantly lower because bone doesn't need to be removed from elsewhere in the body. We also won't have the problem of limited supply that we have when using the patient's own bone."

Currently in pre-clinical trials, Professor Ivanovski says the aim is to trial the new technology in humans within the next one to two years.

Regarding the anticipated cost of treatment, he said that this should be a less costly way of augmenting deficient jaw bone, with the saving expected to be passed onto the patient.

Source: Griffith University

Print Article

Print Article Mail to a Friend

Mail to a Friend