The high diversity of phytoplankton has puzzled biological oceanographers for a long time. Diversity of life abounds on Earth, and there's no need to look any farther than the ocean's surface for proof. There are over 200,000 species of phytoplankton alone, and all of those species of microscopic marine plants that form the base of the marine food web need the same basic resources to grow--light and nutrients.

A study by a team of scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), University of Rhode Island (URI), and Columbia University, published April 13 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveals how species of diatoms--one of the several major types of marine phytoplankton--use resources in different ways to coexist in the same community.

"The diversity of phytoplankton has puzzled biological oceanographers for a long time," says Harriet Alexander, the study's lead author and a graduate student in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography. "Why are there so many different species coexisting in this relatively stable environment, when they're competing for the same resources? Why hasn't a top competitor forced others into extinction?"

To try and answer those questions, Alexander and her colleagues used a novel approach combining new molecular and analytic tools to highlight how similar species utilize resources differently--known as niche partitioning--in Narragansett Bay, R.I.

"The phytoplankton of Narragansett Bay, which is a dynamic estuarine system, have been investigated on a weekly basis since the 1950's, giving us great insight into long term patterns of change," says Tatiana Rynearson, a coauthor and the director of the Narragansett Bay Plankton Time Series at URI. "This study uses that time series, but takes it in an entirely new direction, providing insights into the inner lives of phytoplankton."

Working with water samples collected in conjunction with surveys for the Plankton Time Series from the R/V Cap'n Bert, the research team extracted genetic material called ribonucleic acid (RNA) from the plankton in the bay. RNA sequencing, which was done at the Columbia University Genome Center, allowed the researchers to use the genetic information to determine what organisms were present and what they were doing. The annotation of these RNA sequences via "pattern matching" was facilitated by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation's Marine Microbial Eukaryote Transcriptome Sequencing Project, which has sequenced the genetic material of more than 300 marine species.

In conjunction with the sequencing analysis, the research team developed a new bioinformatic approach that uses data from nutrient amendment experiments to help interpret signals from the environment.

"By adding nitrogen, we can get an idea of what these organisms look like and how they behave when they have plenty of nitrogen," explains Alexander. "Then we would also do the converse, by adding everything that they could possibly want except nitrogen. Creating these extremes in nutrient environment enabled the identification of known and novel molecular markers of nutrient condition for these organisms."

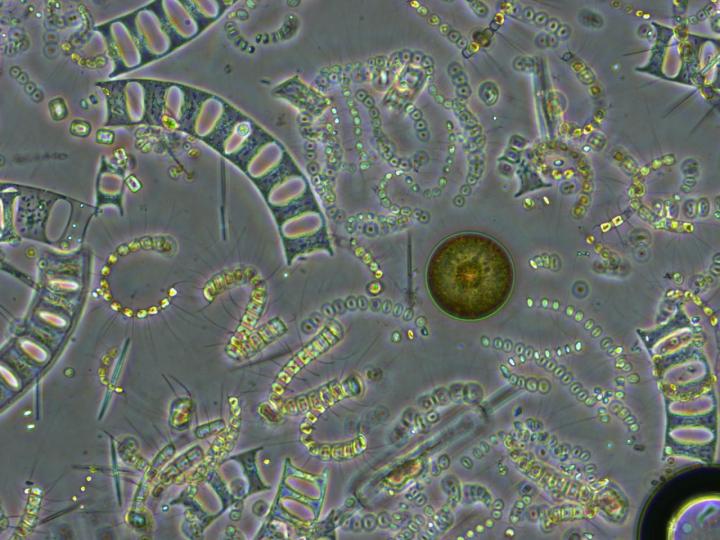

Using these data the researchers observed two species of chain-forming diatoms--Skeletonema spp. and Thalassiosira rotula--coexisting in the same parcel of water, but doing fundamentally different things with available nutrients, specifically nitrogen and phosphorus.

"Skeletonema was the dominant player during our sampling and goes after inorganic nitrogen sources, like nitrate and nitrite. As the less dominant player, Thalassiosira, is doing a lot of work bringing in nitrogen from organic sources, such as amino acids," Alexander says.

"We have long suspected that even closely related phytoplankton must have ways of distinguishing their needs from that of their neighbors, for example using different forms phosphorus or nitrogen, but this has been hard to track in the environment, as most approaches are not species-specific," adds Alexander's advisor and coauthor on the study, Sonya Dyhrman, an associate professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Columbia University.

"Part of the challenge is that you would need to track species-specific patterns in resource utilization to compare one diatom to another," adds Dyhrman. "In this study, a new database that is part of the MMETSP was leveraged to identify species-specific signals, and then Harriet developed a way to normalize those signals to be able to compare quantitatively between species."

Much like human genome sequencing is expanding our understanding of medicine, microbial genomics gives us new insights into how marine organisms function in the ocean and how they are influenced by environmental factors such as climate. The tools developed in this study, point the way to further work that examines how diverse populations of diatoms and other phytoplankton will respond to changing conditions in the future ocean.

Source: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Print Article

Print Article Mail to a Friend

Mail to a Friend