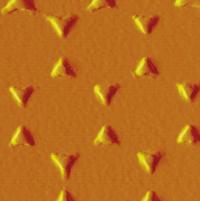

A biosensor made from an array of silver nanoparticles deposited on glass. Nanotechnology is now available in a store near you. Valued for it’s antibacterial and odor-fighting properties, nanoparticle silver is becoming the star attraction in a range of products from socks to bandages to washing machines. But as silver’s benefits propel it to the forefront of consumer nanomaterials, scientists are recommending a closer examination of the unforeseen environmental and health consequences of nanosilver.

“The general public needs to be aware that there are unknown risks associated with the products they buy containing nanomaterials,” researchers Paul Westerhoff and Troy M. Benn said in a report scheduled for the 235th national meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS).

Westerhoff and Benn report that ordinary laundering can wash off substantial amounts of the nanosilver particles from socks impregnated with the material. The Arizona State researchers suggest that the particles, intended to prevent foot odor, could travel through a wastewater treatment system and enter natural waterways where they might have unwanted effects on aquatic organisms living in the water and possibly humans, too.

“This is the first report of anyone looking at the release of silver from this type of manufactured clothing product,” said the authors.

Behind those concerns lies a very simple experiment. Benn and Westerhoff bought six pairs of name brand anti-odor socks impregnated with nanosilver. They soaked them in a jar of room temperature distilled water, shook the contents for an hour and tested the water for two types of silver — the harmful “ionic” form and the less-studied nanoparticle variety.

“From what we saw, different socks released silver at different rates, suggesting that there may be a manufacturing process that will keep the silver in the socks better,” said Benn. “Some of the sock materials released all of the silver in the first few washings, others gradually released it. Some didn’t release any silver.” The researchers will present the specific brands they studied at their ACS presentation.

If sufficient nanosilver leeches out of these socks and escapes waste water treatment systems into nearby lakes, rivers and streams, it could damage aquatic ecosystems, said Benn. Ionic silver, the dissolved form of the element, does not just attack odor-causing bacteria. It can also hijack chemical processes essential for life in other microbes and aquatic animals.

“If you start releasing ionic silver, it is detrimental to all aquatic biota. Once the silver ions get into the gills of fish, it’s a pretty efficient killer,” said Benn. Ionic silver is only toxic to humans at very high levels. The toxicity of nanoparticle silver, said Westerhoff, has yet to be determined.

Westerhoff and Benn did not intend to establish the toxicity of silver. “The history of silver and silver regulation has been set for decades by the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency — we’re not trying to reexamine or reinvent that,” said Westerhoff.

They do hope to spark a broader examination of the environmental and health consequences of nanomaterials, as well as increasing awareness of nanotechnology’s role in everyday consumer goods.

Silver has been used historically since ancient roman times, though its nanoparticle form has only recently appeared in consumer products. Beyond socks, nanosilver appears in certain bandages, athletic wear and cleaning products. Benn suggested that most consumers are unaware of these nano-additions.

“I’ve spoken with a lot of people who don’t necessarily know what nanotechnology is but they are out there buying products with nanoparticles in them. If the public doesn’t know the possible environmental disadvantages of using these nanomaterials, they cannot make an informed decision on why or why not to buy a product containing nanomaterials,” said Benn.

To that end, the researchers suggest that improved product labeling could help. Westerhoff proposes that clothing labels could become like the back of a food packaging, complete with a list of “ingredients” like nanosilver.

Westerhoff and Benn expect to expand their leeching experiments to other consumer products imbued with nanomaterials. They hope to find the moment in each product’s lifecycle when nanomaterials could be released into the environment, as well as developing better detection methods to characterize nanoparticles in water and air samples.

“Our work suggests that consumer groups need to start thinking about these things,” said Benn. “Should there be other standards for these products"”

Source : American Chemical Society

Print Article

Print Article Mail to a Friend

Mail to a Friend