Computers that process information using DNA instead of silicon chips could one day lead to faster, more accurate tests for diagnosing West Nile Virus, bird flu and other diseases. Researchers say that they have developed a DNA-based computer that could lead to faster, more accurate tests for diagnosing West Nile Virus and bird flu. Representing the first "medium-scale integrated molecular circuit," it is the most powerful computing device of its type to date, they say.

The new technology could be used in the future, perhaps in 5 to 10 years, to develop instruments that can simultaneously diagnose and treat cancer, diabetes or other diseases, according to a team of scientists at Columbia University Medical Center in New York and the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Their study is scheduled to appear in the November issue of the American Chemical Society's Nano Letters, a monthly peer-reviewed journal.

"This is a big step in DNA computing," says Joanne Macdonald, Ph.D., a virologist at Columbia University's Department of Medicine. Macdonald led the research team that developed MAYA-II (Molecular Array of YES and AND logic gates) ¯ a "computer" whose circuits consist of DNA instead of silicon. She likens the significance of the advance to the development of the earliest silicon chips. "The study shows that large-scale DNA computers are possible."

"These DNA computers won't compete with silicon computing in terms of speed, but their advantage is that they can be used in fluids, such as a sample of blood or in the body, and make decisions at the level of a single cell," says the researcher, whose work is funded by the National Science Foundation. Her main collaborators in this study were Milan Stojanovic, of Columbia University, and Darko Stefanovic, of the University of New Mexico.

Macdonald is currently using the technology to improve disease diagnostics for West Nile Virus by building a device to quickly and accurately distinguish between various viral strains and hopes to use similar techniques to detect new strains of bird flu. In the future, she suggests that DNA computers could conceivably be implanted in the body to both diagnose and kill cancer cells or monitor and treat diabetes by dispensing insulin when needed.

Scientists have tried for years to build computers out of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), nature's chemical blueprint for life. But getting nano-sized pieces of DNA to act as electrical circuits capable of problem-solving like their silicon counterparts has remained a major challenge.

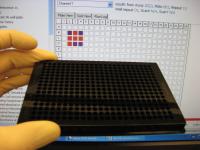

In a series of laboratory demonstrations over a two-year period, Macdonald and her associates showcased the computer's potential by engaging MAYA-II in a complete game of tic-tac-toe against human opponents, winning every time except in the rare event of a tie. Shown in the foreground of the picture above is a cell-culture plate containing pieces of DNA that code for possible "moves"; a display screen (background) shows that the computer (red squares) has won the game against its human opponent (blue).

Composed of more than 100 DNA circuits, MAYA-II is quadruple the size of its predecessor, MAYA-I, a similar DNA-based computer developed by the research team three-years ago. With limited moves, the first MAYA could only play an incomplete game of tic-tac-toe, the researcher says.

The experimental device looks nothing like today's high-tech gaming consoles. MAYA-II consists of nine cell-culture wells arranged in a pattern that resembles a tic-tac-toe grid. Each well contains a solution of DNA material that is coded with "red" or "green" fluorescent dye.

The computer always makes the first move by activating the center well. Instead of using buttons or joysticks, a human player makes a "move" by adding a DNA sequence corresponding to their move in the eight remaining wells. The well chosen for the move by the human player responds by fluorescing green, indicating a match to the player's DNA input. The move also triggers the computer to make a strategic counter-move in one of the remaining wells, which fluoresces red. The game play continues until the computer eventually wins, as it is pre-programmed to do, Macdonald says. Each move takes about 30 minutes, she says.

Source : American Chemical Society

Print Article

Print Article Mail to a Friend

Mail to a Friend