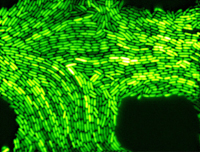

A high level of variation in the amount of green fluorescence protein in individual non-growing E. coli cells surprised synthetic biology researchers at Boston University and the University of California, San Diego An experiment designed to show how a usually innocuous bacterium regulates the expression of an unnecessary gene for green color has turned up a previously unrecognized phenomenon that could partially explain a feature of bacterial pathogenicity.

In a paper published in the Feb. 16 issue of Nature, researchers at Boston University (BU) and the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) reported that computer modeling predicted the new phenomenon before they confirmed it in laboratory experiments. The group led by James J. Collins, a biomedical engineering professor at BU, and Jeff Hasty, a bioengineering professor at UCSD, reported that the rise and fall in the amount of green-fluorescence protein in computer modeling matched the pattern recorded in E. coli cells grown in various laboratory conditions.

The researchers were surprised that cell-to-cell variation in the expression of the synthetic gene increased sharply as growth slowed and then stopped. "We were initially skeptical of our own results because they were so counterintuitive," said Collins. "But our laboratory experiments confirmed this increase in gene-expression variability, or noise, when growth stops. We think there may be some very interesting biology to explore in this situation."

Variability in gene expression could offer distinct survival advantages to a bacterium. Like a cruise ship whose life boats have been stocked with different combinations of food, first-aid kits, rain jackets, and flotation devices, a microscopic version of Survivor could occur in which only those individual bacterial cells with opportune combinations of proteins are able to weather harsh growth conditions in a pond or even inside a human body.

"This phenomenon could be relevant to bacterial 'persisters' - dormant cells that are highly resistant to antibiotics," said Collins. "Many bacterial pathogens can generate these persisters, which over many months can become the source of chronic infections. We don't understand the how persisters arise, but we think this unexpected gene-expression variability in bacterial cells is an interesting phenomenon that should be explored."

The group of researchers came up with the novel finding by using a relatively new research approach that involves the synthesis of simple gene networks, in this case one that produces a green-fluorescence protein. They measured expression of green fluorescence in a laboratory strain of E. coli under different growth conditions where other genes and proteins could potentially complicate the situation. They incorporated that information into a mathematical model.

The authors say their findings demonstrate the value of a so-called "bottom-up" approach to synthetic biology: models of relatively simple cellular processes can be used to predict the behavior of larger, more complex ones.

"We're excited by this study because the model itself led to a counterintuitive prediction that was supported by experimentation," said UCSD's Hasty. "The logical next step is to examine noise in the expression of proteins that would be essential to a bacterium's survival," Hasty said. "We've only begun to get an inkling of how noise in gene expression may be involved in the life of a cell."

Source : University of California - San Diego

Print Article

Print Article Mail to a Friend

Mail to a Friend