An aerial photograph of two right whales in the Atlantic Ocean offshore from Argentina shows the distinctive white markings created by small crustaceans -- known as cyamids or 'whale lice' -- that attach themselves to callus-like material on the whales' heads. University of Utah researchers learned about the evolution of different species of right whales by studying the genes of the 'whale lice' that ride the whales.

Credit: Roger Payne, Ocean Alliance/Whale Conservation Institute.University of Utah biologists studied the genetics of "whale lice" – small crustaceans that are parasites on endangered "right whales" – and showed the giant whales split into three species 5 million to 6 million years ago, and that all three species probably were equally abundant before whaling reduced their numbers.

The five-year study, published in the October 2005 issue of the journal Molecular Ecology, is the first in which the genes of whale lice were used to track the genetic evolution of whales. They are not true lice, but instead are tiny crustaceans named cyamids. The harmless parasites ride the whales their entire lives, so their evolution reflects the evolution of the whales.

"These are the original whale riders," says Jon Seger, a University of Utah biology professor and the study's principal author. "It's a case of the whale riders telling us what the whales did."

["Whale Rider" was a 2002 Oscar-nominated film about the legend of an ancient Maori chief who crossed the sea on the backs of whales, and a modern Maori girl in New Zealand who aspired to become the new chief.]

"Whale researchers have dreamed for years of being able to ride with the whales and see the world they experience," says study co-author Vicky Rowntree, a University of Utah research professor of biology and senior scientist at the Ocean Alliance/Whale Conservation Institute in Lincoln, Mass. "Whale lice have been doing it for millions of years, and can tell us things about the whales we can't learn any other way."

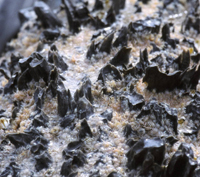

These tiny crustaceans, known as cyamids and nicknamed 'whale lice,' are members of the species Cyamus ovalis. Cyamids, which range from one-fifths to three-fifths of an inch in length, depending on the species, live as parasites on whales. University of Utah biologists studied genes from various species of whale lice to learn about the evolution of different species of right whales, some of which are endangered.

Credit: Vicky Rowntree, University of Utah.By studying certain genes in the whale lice, the researchers showed:

* A single right whale species diverged into three species – North Atlantic, North Pacific and southern ocean right whales – 5 million to 6 million years ago when movements of Earth's tectonic plates formed the Isthmus of Panama, separating the Pacific and Atlantic. That set up warm equatorial currents that kept most blubber-laden right whales from crossing the equator because they could not tolerate the warm waters.

* One southern right whale crossed the equator 1 million to 2 million years ago, leaving evidence of the trip when its whale lice bred with those on North Pacific right whales.

* The highly endangered North Atlantic and North Pacific right whales once may have been as abundant as southern right whales, suggesting their reduced genetic diversity is due to whaling in recent centuries, not some longer-term, deadlier cause. That raises hope for the ultimate recovery of the North Atlantic and North Pacific species

Callosities, or dark callus-like material, are easily visible on the head of this right whale because they are covered by white-colored parasitic crustaceans named cyamids and nicknamed 'whale lice.'

Credit: Mariano Sironi, Institute of Whale Conservation, Buenos Aires.

Seger and Rowntree, who are spouses, conducted the study with Zofia "Ada" Kaliszewska, who graduated the University of Utah and now is a Harvard University graduate student; Wendy Smith, a Utah biology graduate student; and 14 co-authors who collected whale lice or whale genetic material from beached whales around the world.

How Whale-Riding 'Lice' Tell Tales about Whales

Cyamids were nicknamed "whale lice" by early whalers, who often were infested with real head and body lice. Whale lice are related to crabs and shrimp, and cling to the whales' raised, callus-like patches of skin – named callosities – the grooves and pits between callosities, and also to skin in slits that cover mammary glands and genitals. The white whale lice covering the callosities create distinct markings that stand out against the whales' dark skin, making it possible for scientists to distinguish individual whales.

This close-up photograph shows hundreds of tiny, light-colored cyamids, or 'whale lice,' clinging to dark-colored callus-like material on the head of a right whale. University of Utah biologists learned when separate species of right whales evolved by analyzing genetic material from the whale lice.

Credit: Iain Kerr, Ocean Alliance/Whale Conservation Institute.

"Their lifestyle is analogous to that of lice in that they live on the skin of the host and they eat sloughed skin," Seger says. Each whale louse looks vaguely like a miniature crab, ranges from one-fifth to three-fifths of an inch in length, and has five pairs of sharp, hooked claws. About 7,500 whale lice live on a single whale.

Whale lice infest only whales, just as bird lice infest only birds and human lice infest only people. Recent genetic studies of head and body lice have revealed details of human evolution. Whale lice hang onto the whales throughout their lives, so they share a common ecological and evolutionary history with the whales. Genes from whale lice actually may reveal more about the whales than the whales' own genes do, because the parasites are much more abundant and reproduce more often than whales. As a result, the parasites have much greater genetic diversity and scientists have more mutations to track.

The Utah research focused on genes found in mitochondria – the power plants of cells – and that mutate at a high rate, acting like a clock to reveal when evolutionary events happened. The scientists calibrated the clock by comparing genes from whale lice with related snapping shrimp.

The Utah biologists extracted DNA from whale lice, determined the sequence of the genetic components in a particular mitochondrial gene, and then built family trees to show the relationships among whale lice.

The same three whale louse species – Cyamus ovalis, Cyamus gracilis and Cyamus erraticus – were thought to infest each of the three different species of right whale. But the new study revealed that like the whales, each whale louse species also split into three species, so North Pacific, North Atlantic and southern ocean species of right whales each are infested by three distinct species of cyamid. That tripled – from three to nine – the number of cyamid species infesting right whales.

The Right Whale – for Extinction?

Right whales – which can reach 60 feet and 70 tons – were named because "they were the 'right' whale to kill, the first whale to be commercially hunted" 1,000 years ago off Spain; their blubber made their carcasses float for easy recovery, Rowntree says.

Two of the three species of right whales are in danger of extinction. A recent study estimated only 350 remain in the North Atlantic. Rowntree says about 200 survive in the North Pacific, while the Southern Hemisphere population of 8,000 to 10,000 whales is growing 7 percent per year and recovering from whaling.

When whaling began in the Southern Hemisphere in the 1700s, there were an estimated 40,000 to 150,000 right whales there, Rowntree says.

North Atlantic right whales have lower genetic diversity than southern ocean right whales. But the new study showed "the genetic diversity of whale lice is virtually as great for the North Atlantic right whale as for the southern right whale, suggesting that historically (but before whaling) the North Atlantic right whale population was comparable in size to that in the Southern Hemisphere," Seger says. "This suggests that the reduced genetic diversity of North Atlantic right whales happened recently, possibly due to whaling, not because the whale population was small even before whaling."

Whale louse populations correlate with population sizes of right whales, so if North Atlantic right whales had small populations before whaling, the diversity of their whale lice would not be as great as those on the southern right whales.

Limited data from North Pacific whale lice suggest right whales also were abundant there before whaling began, in line with early whaling records, Rowntree says.

Small population size can be harmful because it is impossible to avoid inbreeding and an increased risk of genetic disease. The study raises hope for endangered Northern Hemisphere right whales by suggesting that their reduced genetic diversity is a relatively recent phenomenon and perhaps not as severe overall as it appears to be in the particular genes that were studied, Seger says.

One Whale Species Became Three as Oceans Separated

Some 20 million years ago, North and South America were separated by deep seas, but 18 million years ago, undersea volcanism slowly began forming a volcanic island chain. By 3 million years ago, the chain formed solid land, the Isthmus of Panama, linking the two continents. By 5 million or 6 million years ago, the sea between the two continents was so shallow that whales could not swim between the North Pacific and North Atlantic, Rowntree says. Changing circulation patterns established warm currents that discouraged right whales from moving between southern and northern oceans.

"Right whales have such thick blubber they can't cross the equator," Rowntree says. "The waters are too warm. They can't shed heat."

Seger says: "The genetics of whale lice show conclusively that the three species of right whales have been isolated in the North Pacific, North Atlantic and Southern Hemisphere for about 5 million to 6 million years," with a possible range of error from 3.6 million to 9.9 million years.

That is consistent with previous studies of the right whales' genes. One limited study suggested North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) and southern (Eubalaena australis) right whales became distinct species 3 million to 12 million years ago. A more complete study suggested North Pacific right whales (Eubalaena japonica) diverged from southern right whales 4.4 million years ago, give or take 2.5 million years.

The new study revealed a fascinating detail. About 1 million to 2 million years ago, at least one southern right whale – and no more than a few – managed to cross the equator and join other right whales in the North Pacific. The biologists reached that conclusion because they found that Cyamus ovalis whale lice in the North Pacific are much more closely related genetically to southern Cyamus ovalis than either population is to those in the North Atlantic. Another species, Cyamus erraticus, does not show such a pattern; those whale lice in all three oceans are all more distantly related.

The simplest explanation is that a single southern right whale crossed the equator and mingled with North Pacific right whales. Some of the abundant Cyamus ovalis whale lice jumped from the southern whale to northern whales, but the less common Cyamus erraticus, which lives mainly in genital areas, did not.

Despite the barrier posed by warm water, climate has changed over the ages and "probably there were times when the equatorial waters weren't as hot as they usually are, and some adventurous juvenile male crossed the equator," Rowntree says.

Source : University of Utah

Print Article

Print Article Mail to a Friend

Mail to a Friend