Humans with an appreciation of beauty may have marveled for millennia at the artistry of a darting hummingbird, but scientists announced today that for the first time they can more fully explain how a hummingbird can hover.

Humans with an appreciation of beauty may have marveled for millennia at the artistry of a darting hummingbird, but scientists announced today that for the first time they can more fully explain how a hummingbird can hover.

Using a powerful technology that was originally developed for engineering, researchers were able to exactly document the movement of air around a hummingbird's wings and show how its flight is accomplished with the body structure of a bird but some of the aerodynamic tricks of an insect.

This gives it an ability to hover almost indefinitely - an evolutionary advantage in feeding on plant nectar that no other bird has - and an elegance that has charmed people for generations.

The findings were published today in the journal Nature, by scientists from Oregon State University, the University of Portland and George Fox University.

"For decades most researchers thought that hummingbirds had the same flight mechanisms as insects, some of which can hover and dart around in the same way," said Douglas Warrick, an assistant professor of zoology at OSU. "But a hummingbird is a bird, with the physical structure of a bird and all of the related capabilities and limitations. It is not an insect, and it does not fly exactly like an insect."

Flying insects have wings that are almost flat. They gain lift with two mirror-image halfstrokes as the wing moves back and forth in a figure eight pattern, producing nearly equal lift during the downstroke and upstroke. Hummingbird wings move in a similar pattern, and like insects, a hummingbird can invert its wings – turn them upside down during the upstroke – a fair amount more than an average bird. Thus, is has long been assumed that hummingbirds, like insects, were developing equal amounts of lift during both halves of the wing cycle.

But Warrick and his colleagues, Brett Tobalske at the University of Portland and Don Powers at George Fox University, suspected the similarities were misleading.

Bird wings are quite different than those of insects. The bone structure of bird wings, in fact, in some ways is more like that of a human arm that an insect wing. Both birds and humans have a single larger upper bone in their limb called the humerus, and two bones in the lower limb called the radius and ulna. The "fingers" in birds have been welded together into a structure called the manus, onto which most of their feathers are attached.

"We looked at hummingbird flight for 70 years with high speed cameras, but still could only make assumptions and educated guesses about what was happening," Warrick said. "The technology we have now is like a big new telescope showing us parts of the sky we never saw before."

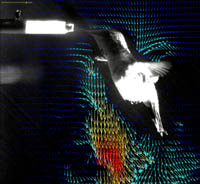

That technology, Warrick said, is called digital particle imaging velocimitry, which has never before been applied to the study of hovering birds. This system atomizes olive oil into microscopic droplets that are so light they move instantly with the slightest movement of air - and a pulsing laser then illuminates the droplets for incredibly short periods of time that can be captured by cameras, and illustrate exactly the swirling movement of air left by a hummingbird's wings. The research was done with rufous hummingbirds, a migratory species common in Oregon.

"The images we obtained were astonishing," Warrick said.

They showed that because of the limitations of its wing structure, a hummingbird develops only 25 percent of its weight support during the upstroke, while producing the remaining 75 percent during downstroke.

While not the equality of half-strokes that insects exhibit, it's still very different from other birds, which produce virtually all of their flying lift on the downstroke. And a hummingbird also taps into "leading edge vortices," an aerodynamic mechanism commonly taken advantage of by insects, to provide some of this lift on the downstroke. The tiny swirls of these vortices were clearly illustrated by the new laser images of hummingbird flight.

"What the hummingbird has done is take the body and most of the limitations of the bird, but tweaked it a little and used some of the aerodynamic tricks of an insect to gain a hovering ability," Warrick said. "They make use of what is, in other birds, an aerodynamically wasted upstroke. Coupled with taking advantage of leading edge vortices – which you can only produce to substantial effect if you're small – and voila, you're hovering for as long as you want."

Hummingbirds can hover well enough for a sustained period of time to have an evolutionary advantage, Warrick said.

"It may not be the elegant, symmetrical flight of insects, but it works," he said. "It's good enough. Hovering is expensive, more metabolically expensive than any other type of flight, but as insects have found, nectar from a flower is an even bigger payoff."

"Hummingbirds arrived at the ability to hover from a totally different evolutionary path, and they borrowed a few aerodynamic concepts from insects along the way," he said. "Natural selection made use of what materials were available – a bird body – and made a hovering machine."

Source : Oregon State University

Print Article

Print Article Mail to a Friend

Mail to a Friend